In the News

Toxic dust and asthma plague Salton Sea communities

-

Focus Areas

Chronic Disease Prevention, Environmental Health -

Issues

Asthma -

Programs

Tracking California

Kaylee Pineda likes to be outdoors. She rides her bike, plays Little League baseball and enjoys swinging on the monkey bars at school.

But when the wind picks up and the air turns hazy, she knows she needs to stay indoors. The dust can suddenly trigger her asthma and leave her gasping for air.

“I feel like my chest tightens,” Kaylee said. “My heart starts pumping.”

Kaylee, who is 9 years old, uses an inhaler every morning before going to school and every night before going to bed. Sometimes, when her chest hurts and she struggles to breathe despite the medication, her mother drives her to the hospital.

A serious asthma crisis is afflicting communities around the Salton Sea. The southeastern corner of California has some of the worst air pollution in the country, where dirt from farmland and the open desert mixes with windblown clouds of toxic dust rising from the Salton Sea’s receding shores.

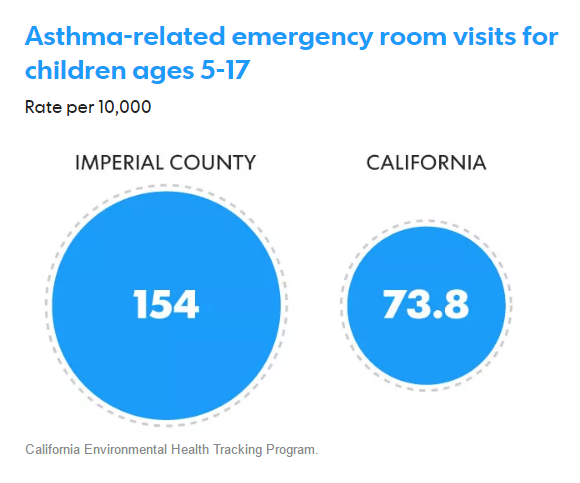

Imperial County already has the highest rate of asthma-related emergency room visits for children in California. And the problem is about to get much worse.

At the end of this year, the sea will begin to shrink more rapidly under a water transfer deal that’s abruptly cutting off a large portion of the Colorado River water that flows into the lake. Thousands of acres of lakebed will be left exposed in the coming years, sending bigger clouds of fine dust wafting into the air in the Imperial and Coachella valleys – which is laced with pesticides such as DDT and heavy metals that have accumulated in the lake over decades.

California’s 10-year plan for the sea calls for building ponds and wetlands on sections of the exposed lakebed, or playa. But those projects will cover up less than half of the more than 60,000 acres of playa that will be left dry over the next 10 years.

Kaylee’s mother, Eva Pineda, said she’s afraid that more dust in the air will be disastrous for people’s health.

“I know asthma is going to get worse for the kids here,” Eva said. “All those little particles are going to be flying around here and it’s going to go into everybody’s lungs.”

All three of her children have asthma, and many other people in the area suffer from allergies, chronic sinus infections and other respiratory illnesses. Eva said she hopes something gets done to combat the dust.

“It should be taken care of because it’s really going to affect us,” she said. “If it doesn’t get fixed, there’s going to be a lot of ill people with breathing problems.”

The costs of coping with asthma

Every weekday morning at Westmorland Union Elementary School, a brightly colored flag is raised on the flagpole. If the flag is green, the air quality is good. If it’s yellow, it signals to parents and children that the air pollution level is “moderate.”

Kaylee checks the color of the flag each morning when her mother drops her off.

“Yellow is be careful. Orange is people who have asthma, stay in. Red is for everybody, stay in,” Kaylee said. “If it’s super windy, I stay in the office. Or I just stay in the classroom.”

She knows a green flag means it will be a good day and she’ll be able to play outside with her friends during recess.

The school in Westmorland, flanked by farmland south of the Salton Sea, is one of 10 schools in the Imperial Valley that use the flags. Many parents also receive emailed alerts from the Imperial County Air Pollution Control District when pollution reaches unhealthy levels.

A total of 64 children have asthma at the school – 17 percent of the student body. Students’ inhalers are kept in the office, where the children come if they have trouble breathing.

Eva remembers her stepdad would take the family fishing at the sea.

“We would go swimming in there,” she said. “It was beautiful.”

Now people in Westmorland complain about the smells of decay that waft from the sea. The last time Eva visited the lake, she saw dead fish scattered along the shore. She hasn’t been back in years, even though the sea lies just several miles away.

Kaylee recently went on a field trip to the Salton Sea with her third-grade class. She enjoyed watching the birds and running around with her classmates.

“It was a nice day, a little bit windy but not that much for my asthma,” Kaylee recalled, sitting in her living room. She added, pleased: “I didn’t use my inhaler.”

Kaylee has learned to measure her days by how well she keeps her asthma in check.

She was first diagnosed with asthma when she was 5. Since then, she has been regularly using a nebulizer and taking puffs from inhalers.

Her asthma is often triggered by a fit of coughing. When it won’t go away, her mother takes her to the emergency room – usually two or three times a year.

Once last year, Kaylee was hospitalized for three days until she was well enough to go home. The previous year, she had a cold and needed to stay in the hospital for five days.

The hospital bills have added up over the years. Eva previously paid between $700 and $800 every time Kaylee went to the ER, and $3,800 for the five-day hospital stay.

That was when she had medical insurance through her previous job at a KFC restaurant. Now Eva is unemployed. Her husband died of cancer in 2015 and she’s been relying on Social Security benefits while making plans to study accounting. She’s thankful that Medi-Cal now covers Kaylee’s medical bills.

On a recent afternoon, Kaylee went about her routine to prepare for a Little League game. She sat inhaling and exhaling into a mask, her nebulizer humming.

Outside her house, trees were bending in the gusty wind and haze filled the air.

Eva said she was surprised the baseball game hadn’t been canceled. Then her phone rang with a call from the coach, who confirmed it was called off due to the weather.

“Yeah, it’s really bad,” Eva said. “When it gets this bad, this is what happens.”

Years of inaction and frustration

The Salton Sea is California’s largest lake and has been sustained by water running off farmland in the Imperial Valley for more than a century. The lake was created between 1905 and 1907, when floodwaters from the Colorado River burst through canals and filled the low-lying basin in the desert.

The sea’s coming decline stems from the growing strains on the Colorado River. Under the water transfer deal, which was approved in 2003, the Imperial Irrigation District is selling increasing quantities of water to growing urban areas in San Diego County and the Coachella Valley.

The agreement called for the Imperial district to send “mitigation water” from its canals into the sea through 2017 – a period intended to give state agencies time to prepare for dealing with the effects. At the end of this year, that flow of water will be cut off and the lake will recede more rapidly. Over the next 30 years, the sea is projected to shrink to about a two-thirds of its current size.

The water transfer deal isn’t the only thing pushing the Salton Sea toward a drier future.

The Colorado River is severely overallocated and has dwindled during 17 years of severe drought. Scientists have projected that human-caused climate change could cause the river’s flow to decrease by 35 percent or more this century.

Gov. Jerry Brown’s administration released its 10-year plan for the Salton Sea in March after years of delays and unrealized plans, and following pressure by the Imperial district, which has repeatedly warned it won’t support a Colorado River drought deal until the state delivers a viable “roadmap” for the sea.

While the state’s $383-million plan and an initial $80 million in funding have drawn praise as important first steps, some activists say they’re concerned that much more needs to be done – and that leaders in Sacramento have long neglected the worsening health problems in one of California’s poorest regions, where Latinos make up the majority of the population and many are farmworkers.

“Government ignored the problem,” said Luis Olmedo, who leads the Brawley-based nonprofit Comité Cívico Del Valle. “It’s just poor planning and basically ignoring a predominantly low-income disadvantaged community.”

Olmedo’s group has promoted the flags program in schools to alert students and parents to air pollution. His organization also sends health workers to the homes of asthma patients to help them pinpoint hazards in their homes and their surroundings.

Last year, his group helped install a new network of 40 air monitoring devices across the Imperial Valley. Olmedo said he views the initiative, which was funded by a federal grant, as an environmental justice project that fills in gaps in the data collected by government agencies and allows people to sign up for local air pollution alerts.

Olmedo said controlling dust from the Salton Sea should be a priority, along with reducing threats from other pollution sources such as farmers burning their fields.

“We shouldn’t have this level of asthma,” Olmedo said. “It is a crisis. It’s an emergency. It needs to be dealt with.”

Researchers have been warning for years that if actions aren’t taken to control dust, the sea will become a costly disaster.

The Pacific Institute, a think tank focused on water issues, estimated in a 2014 report that without significant steps to address the sea’s problems, the costs over the next 30 years could range from $29 billion to $70 billion – including higher health care costs for illnesses and lower property values.

Zoë Meyers/The Desert Sun |

The group estimated the costs of unchecked windblown dust on public health could reach as high as $37 billion by 2047, worsening asthma and other illnesses ranging from lung cancer to cardiac disease. Within three decades, the group warned, the exposed lakebed could be releasing as much as 100 tons of dust into the air per day.

More than 18,000 acres of dry, salt-encrusted shoreline have already been left exposed as the lake has receded over the past two decades.

When winds rake across the lakebed, sand blows in drifts and dust billows into the air in brown clouds. It settles in neighborhoods downwind of the sea, in towns from Calipatria to Brawley to Westmorland, blanketing lawns and sidewalks and leaving cars coated with grime.

For Karol Ruelas, an 18-year-old senior at Brawley Union High School, a windy morning can trigger fits of coughing. On a recent day when Brawley was under an alert for unhealthy air during a dust storm, Ruelas stayed inside most of the day.

“The Salton Sea has affected my health greatly,” Ruelas said. “Sometimes it’ll get to a point where I cannot breathe because of the dust from the Salton Sea.”

She has severe allergies and chronic sinus infections, or sinusitis. She swallows a pill every morning and takes more if she has an attack. Sometimes she needs to get a shot to control her breathing problems.

“I’ve actually had points where I’ve been enjoying my day and then it gets windy and then my airways fill completely back up,” Ruelas said. “And I remember the first time, I absolutely panicked. I was like, ‘Oh my God! Why can’t I breathe?’”

Her doctor has recommended surgery for her sinusitis. In the meantime, he’s suggested she avoid exercising outdoors and stay inside as much as possible. The doctor also recommended she consider moving away to an area with cleaner air.

She told him she prefers to stay in the Imperial Valley, even though it may involve staying on medication.

“This is my home and I don’t want to leave it,” Ruelas recalled telling him.

She hopes to eventually become a nurse here and help others who suffer from asthma and allergies. She’s concerned and frustrated, though, by the lack of action so far.

“If nothing is done and they allow the Salton Sea to recede and expose even more sand, it will get definitely worse. My attacks will definitely get longer and more often,” Ruelas said. “I’m hoping that action will be taken.”

Studying the dust threat

The water that flows into the Salton Sea from the Alamo River and the New River contains a mix of pollutants, including pesticides in agricultural runoff and sewage effluent from Mexicali.

Lisa Valencia works with Humberto Lugo of Comite Civico del Valle to change the filter on an air monitor at Calipatria High School. Zoë Meyers/The Desert Sun

|

Over the years, researchers studying water and sediment samples from the sea have found heavy metals such as mercury, copper and arsenic, and pesticides such as DDT.

Until recently, no detailed studies had ever been conducted on the makeup of the dust.

Now two researchers from the University of Southern California are carrying out the first study of its kind to discover what’s in the dust. They’ve scooped up soil samples from the playa, sealed it in plastic bags and sent it to researchers at the University of Iowa, where the dust is analyzed to check for heavy metals, pesticides, bacteria and fungi.

They’ve also installed devices to collect airborne dust at schools in Calipatria, Westmorland and Brawley.

“Other researchers have detected toxic metals in samples taken directly from the playa, but we don’t know if these contaminants are being carried in the dust and making their way into the communities,” said Shohreh Farzan, a professor of preventive medicine at USC’s Keck School of Medicine. “If this is happening, breathing that metal-laden dust could be particularly toxic.”

The study by Farzan and fellow USC professor Jill Johnston is being funded through a grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. They’re also conducting a community health survey, using questionnaires to ask families about asthma and other ailments such as wheezing, coughing and sleeplessness.

“You have a community that’s really burdened by respiratory health issues,” Johnston said. “When you have that issue and then on top of that you’re putting potential impacts of the Salton Sea, this community can be really vulnerable.”

California has one comparable example of a lake that turned into a costly health hazard: Owens Lake, which dried up in the 1920s after water was diverted to supply Los Angeles. The dry lakebed on the east side of the Sierra Nevada became a major source of air pollution, and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power has spent $1.8 billion in Owens Valley, primarily to control dust.

Because the Salton Sea is much bigger than Owens Lake and in an area with a larger population, the long-term costs could end up being higher.

Some of the dust-control methods that state officials plan to employ around the Salton Sea have been used previously at Owens Lake, such as flooding the lakebed to create shallow ponds or plowing the dry playa.

The Imperial Irrigation District has been experimenting with plowing stretches of the southern shore that were underwater a decade ago.

On a recent morning, a tractor pulled a plow across a flat expense of lakebed, cutting deep furrows in the sunbaked soil. This “surface roughening” project near the dry boat ramp at Red Hill Bay is one portion of about 800 acres that have been plowed.

The plowing creates furrows in the soil about three feet deep from top to bottom, forming dust-trapping ridges. “The dark soil in the bottom of the furrow is moist and soft and fine-textured — a type of soil that forms stable clods.”

So far the irrigation district has spent $200,000 on the project, using funds made available through the water transfer deal.

Jessica Lovecchio, who is leading the project, said her team is gathering detailed information on how effective the plowing is and how long the furrows will hold up before it’s necessary to plow again. Plowing doesn’t work as well in sandy areas, so in those spots workers have been planting seeds of salt-tolerant plants. When the plants take root, they form natural barriers that block windblown dust.

“We can come in and be proactive and make sure this area doesn’t blow dust,” Lovecchio said, standing near the tractor. “If we’re able to get out now and do something on the ground to eliminate dust, that is just that much less dust in the future.”

These kinds of waterless measures will likely play an important role given the large gap between the areas where ponds and wetlands are to be built and the vast expanses of lakebed that will be left exposed. Other methods may include spraying chemicals to create a hard crust or laying down bales of hay, logs or woodchips to create windbreaks.

The state’s 10-year plan focuses on the northern and southern shores and doesn’t include any ponds along the western or eastern shores. In those areas, where there is no river inlet nearby to supply water, more of the shoreline could end up etched with plowed furrows.

Originally published by The Desert Sun

More Updates

Work With Us

You change the world. We do the rest. Explore fiscal sponsorship at PHI.

Support Us

Together, we can accelerate our response to public health’s most critical issues.

Find Employment

Begin your career at the Public Health Institute.