Update

The Forgotten Victims of Officer-Involved Shootings

-

Focus Areas

Healthy Communities -

Issues

Violence Prevention -

Programs

Berkeley Media Studies Group

His name was Stephon Clark, and he was 22 years old. He was a father, a son, a neighbor, a friend, and a member of his community.

His name was Stephon Clark, and he was 22 years old. He was a father, a son, a neighbor, a friend, and a member of his community.

He was in his grandparents’ backyard in Sacramento when police shot 20 rounds of bullets at him, killing him, on the evening of March 18.

As a mom and a Californian, I was moved by the tragedy. As a media researcher, I know it is not unique. Clark was the 225th person shot by police this year alone (at publication time, that number had risen to 244). Almost 1,000 people were killed by police in 2017.

But many people probably would not know how high the numbers are because, although other forms of gun violence dominate the news, when a police officer shoots someone, news outlets sometimes don’t report the story.

Accurate and complete news coverage is important because we can’t mourn victims unless we know about their deaths, and we can’t fix a problem we aren’t told about. To support communities as they grapple with the death of yet another young man of color shot by the police, PHI’s Berkeley Media Studies Group (BMSG) set out to understand more about how the news commemorates or ignores those who have been killed.

We examined the data on fatal California officer-involved shootings kept by the Washington Post and Killed by Police. These sites collect data from “news reports, public records, social media and other sources,” so they may not represent the total number of killings. We found no other databases that track officer-involved shootings across the country, though individual police departments have released data about incidents in their jurisdictions.

We cross-referenced each shooting with news from 75 newspapers (and their online equivalents) from around California.* We found 162 officer-involved fatal shootings in California in 2017 and 330 news articles about them.

For almost one-third of all shootings, we found no news coverage in the outlets we examined. More than half of the victims of the shootings without news coverage were African American and Latino men (at least 53 percent, though there could be more because there were 11 incidents without coverage where the race of the victim was not indicated in the Washington Post database).

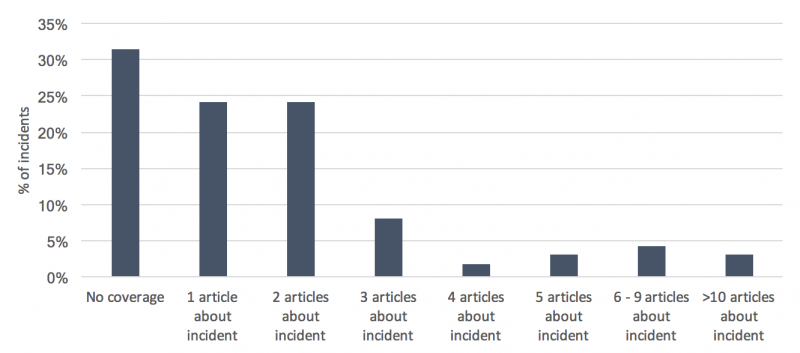

How many articles did officer-involved shootings generate in California newspapers in 2017? (n=162 incidents)

When stories about officer-involved shootings did appear, they were usually brief and provided little background information. The coverage included only a few articles about each killing: Nearly half of the fatal police-involved shootings in 2017 produced only one or two brief stories (48 percent of incidents). The few cases (10 percent) that generated five or more articles drew attention because the victim’s family continued to call for justice (as in the case of Desmond Phillips from Chico, who, like Stephon Clark, was in a family home when he was shot), or because the “suicide by cop” details of the case inspired discussion about teen suicide.

When most of the victims whose stories we don’t hear are Black and Latino, the unfair burden of police violence that these communities suffer is also harder to see. These findings (and observations from our partners and colleagues around the country) suggest that our key public narratives—including our news narratives—about police violence may be missing important pieces of the story.

Of course, there are still a lot of questions to be answered:

- What about non-fatal shootings?

- What does coverage from television and social media look like?

- What information should be part of the news narrative if we are to better understand what’s needed to build communities where everyone is truly safe?

- What is the role and responsibility of journalists, of community members, of allies, of leaders, of politicians, of each one of us?

We hope we’ll have the chance to explore the answers. In the meantime, Berkeley Media Studies Group will continue monitoring the news and asking questions—about Stephon Clark’s story and anyone whose stories come after his.

Advocates—and anyone who wants to know the true toll of officer-involved shootings—must keep insisting that we see the stories of anyone killed by police whose death doesn’t make the front page.

Methods

*Based on data from the Washington Post and killedbypolice.net, we used the Lexis-Nexis database to search all California newspapers for any reference during 2017 to the shooting victim, along with the word “police.” When we were unable to find the name of the victim, we searched Google News and Lexis-Nexis for the phrase “officer-involved shooting” or “police shooting,” along with the location of the incident and the approximate date to find the name of the victim. We then read each article to determine whether or not it was related to the specific police killing.

Originally published by Berkeley Media Studies Group

More Updates

Work With Us

You change the world. We do the rest. Explore fiscal sponsorship at PHI.

Support Us

Together, we can accelerate our response to public health’s most critical issues.

Find Employment

Begin your career at the Public Health Institute.