Public Health Over Punishment: Media tools for communicating about police and prison budgets

- Heather Gehlert and Katherine Schaff

-

Focus Areas

Healthy Communities -

Issues

Violence Prevention -

Expertise

Media Advocacy & Communications -

Programs

Berkeley Media Studies Group

How advocates can use social math and other tools of media advocacy to communicate about police and prison budgets

At Berkeley Media Studies Group, we often start our trainings by asking participants, if the only way people knew about your issue was from the news, what would they know? What wouldn’t they know? Regardless of issue, what’s often hidden from view are the years of organizing and hard work that build the foundation for the more visible moments of social change. This holds true for the recent rise in news coverage on police violence and the focus on police budgets that activists pushed for after the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade.

Across the country, communities have been organizing for years to address police violence, using tactics ranging from direct action to op-eds to build the momentum for change. Although criticism of cities and counties continually increasing law enforcement budgets while cutting funding for schools, public health, and other parts of our social fabric is not new, the volume of news coverage has increased. The ensuing debate — and media expressing confusion — about what it means to defund the police is not unexpected, as our current system is deeply entrenched in our budgets and our minds. However, through the use of social math and other tools of media advocacy, organizers are finding compelling ways to show what the world could look like if budgets were focused on healing communities and creating equitable practices that support health.

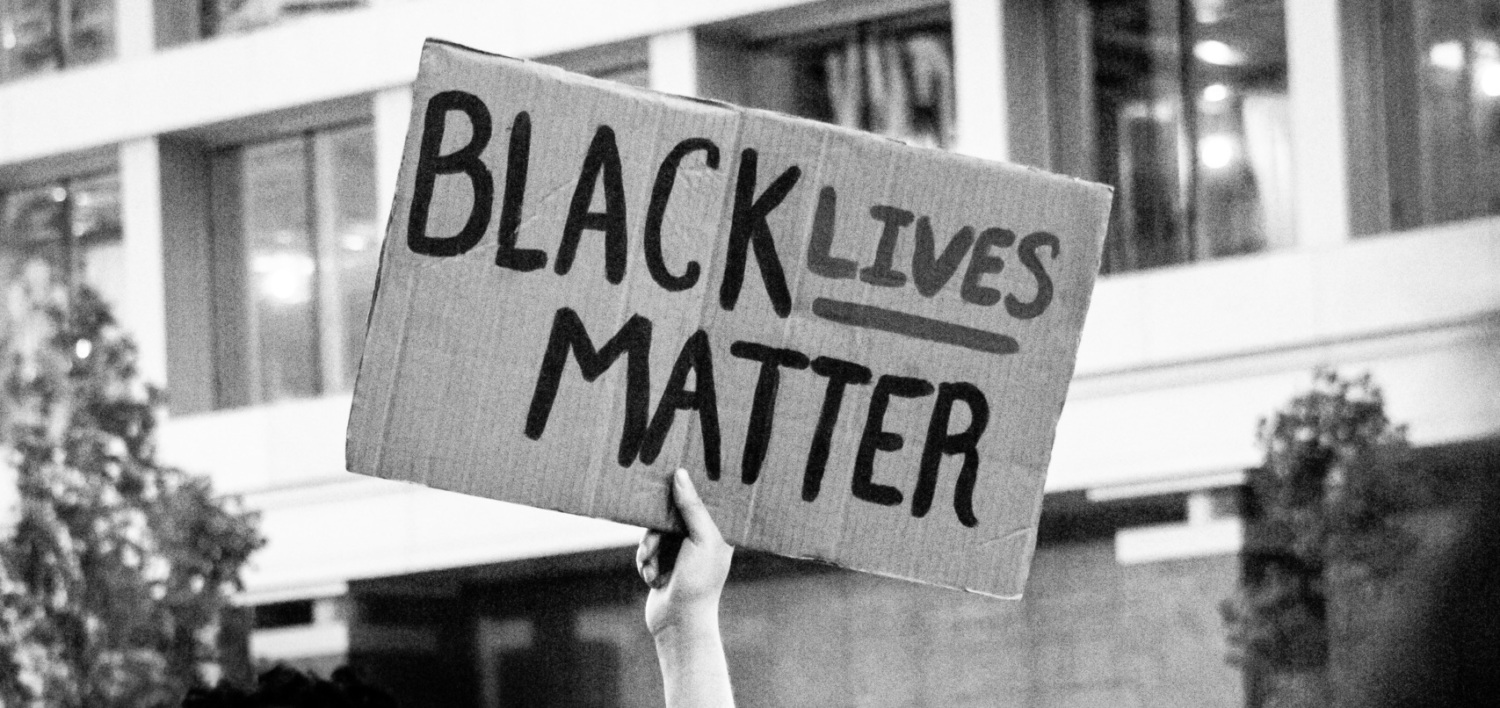

That’s exactly what local advocates did when they crafted an op-ed this summer to renew the call to defend Black lives, clarify demands, and increase support for reallocating police funds. Titled “Alameda County Should Create a Budget that Shows Black Lives Matter,” the op-ed showcases many strategies that advocates can replicate as they push for transforming local budgets to reflect a commitment to racial and health equity.

To learn more about the process behind the op-ed, BMSG talked with the lead author, Amber Akemi Piatt, who directs the Health Instead of Punishment Program at Human Impact Partners (HIP), a nonprofit that is trying to build systems within communities that promote public health and racial justice. Piatt’s program works to examine budgets for policing, immigration enforcement, and incarceration — and to shift taxpayer dollars in ways that prioritize health. Piatt also participates in Decarcerate Alameda County, a coalition that similarly aims to invest in community health instead of cops. Here are some key lessons and highlights from our conversation:

1. Piggybacking off national news can help reinvigorate local issues.

Community advocates were already working to reallocate law enforcement and jail funds in ways that more effectively support health and safety in Alameda County when news broke of the police killings of Floyd, Taylor, and McDade — and the ensuing uprisings against anti-Black racism. Advocates had already developed media campaigns for many local efforts but wanted to create a deeper understanding of the link between county budgets and racial justice. So, amid the country’s collective organizing — and outrage — Decarcerate Alameda County found an opportunity to spotlight local action.

“We wanted to connect that national movement work with some of the county-level organizing that we’ve been doing for years — and specific solutions that we can budget for [now],” said Piatt.

2. Media advocacy is stronger when paired with community partnerships.

Although Piatt took the lead on the op-ed, she noted that her ability to do so “came from years of organizing and understanding what’s important on the values level and on a demand level.” Because of her relationships with other partners in the community, she knew how to create content that would reflect their collective asks; she also had the trust required to get their attention — and feedback — on a Sunday afternoon. She described it as a “collective effort,” with about a dozen people involved in editing the op-ed prior to submission. In fact, Piatt said that one of the organizers of a Black Lives Matter car caravan led by the Anti Police-Terror Project edited the article from her car during the protest. Without strong relationships already in place, that likely wouldn’t have been possible.

3. Creative comparisons can help readers visualize complex issues.

It’s common for reporters to reference bloated budgets or to cite large figures that are hard to grasp. Social math, or the practice of breaking down large numbers, can make dense data more meaningful for lay audiences.

“It’s like putting a quarter next to a picture of something,” Piatt said. “If you want to give size reference, sometimes if you just take a picture of a bird and you don’t have that bird next to some other object for reference, people don’t understand the size. And so … we have said over and over and over that the Alameda County sheriff’s office budget is bloated, that it’s outsized and inappropriate. But that only gets us so far in being able to conjure a picture of what that means. Even though Alameda County does have a publicly available operating budget, it’s still actually incredibly wonky and difficult for people to understand.”

In the op-ed, Piatt and her partners put social math to work by using a strategic comparison: The additional $318 million preliminary budget that the Alameda County Board of Supervisors approved in May for the Santa Rita Jail, she explained, is “nearly three times the Alameda County Public Health Department’s entire annual operating budget.”

That comparison expands the frame to include health. And, Piatt explained, it “brings a shock factor to our audiences in a way that even saying ‘three hundred, eighteen million dollars’ does not.”

4. Personalizing large numbers, or restating them in terms of time or place, can also help simplify statistics.

Most of us do not have multi-million or billion-dollar household budgets, so it can be hard to know just how large certain numbers are. Recasting those figures, as data journalist Mona Chalabi often does, can make statistics more relatable. For example, to put the New York Police Department’s $5.9 billion budget into perspective, she tallied how much money they spend per day (roughly $16.2 million), per hour ($675,920), and per minute ($11,265). To further reinforce the magnitude of funds, she calculated how much money the NYPD spends in the time it takes to cycle across commonly used bridges: $73,129.

Using a similar tactic, Piatt noted in the op-ed for the San Francisco Chronicle that the additional $318 million in funds for the Santa Rita Jail are on top of the approximately $137,080 per year that the county already spends to keep people locked up.

5. Money isn’t the only way to communicate costs.

Although bank accounts and spreadsheets may come to mind for many people when thinking of budgets, Piatt is quick to remind us that finances are only one way to measure the costs of budgetary decisions.

“It’s important to highlight the economic consequences of continuing to invest in harmful systems of criminalization and incarceration,” she said. “But it also doesn’t always capture the human cost of living a life under terror of, and fear of, being harmed … and attempting to heal from having experienced [violence] yourself, or having lost a loved one to police violence.”

A recent op-ed in The New York Times offers an excellent example of articulating those human costs and fears; it does so by elevating the authentic voice of Rick Blake, the uncle of Jacob Blake, who was paralyzed after being shot seven times in the back by a police officer in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

“We as an African-American community are weary,” Blake wrote. “We are tired of this fight to ‘prove’ the value of our humanity — a truth that should be self-evident. … With exhausted bodies and voices, we continue to pay a high price.”

6. Elevate solutions.

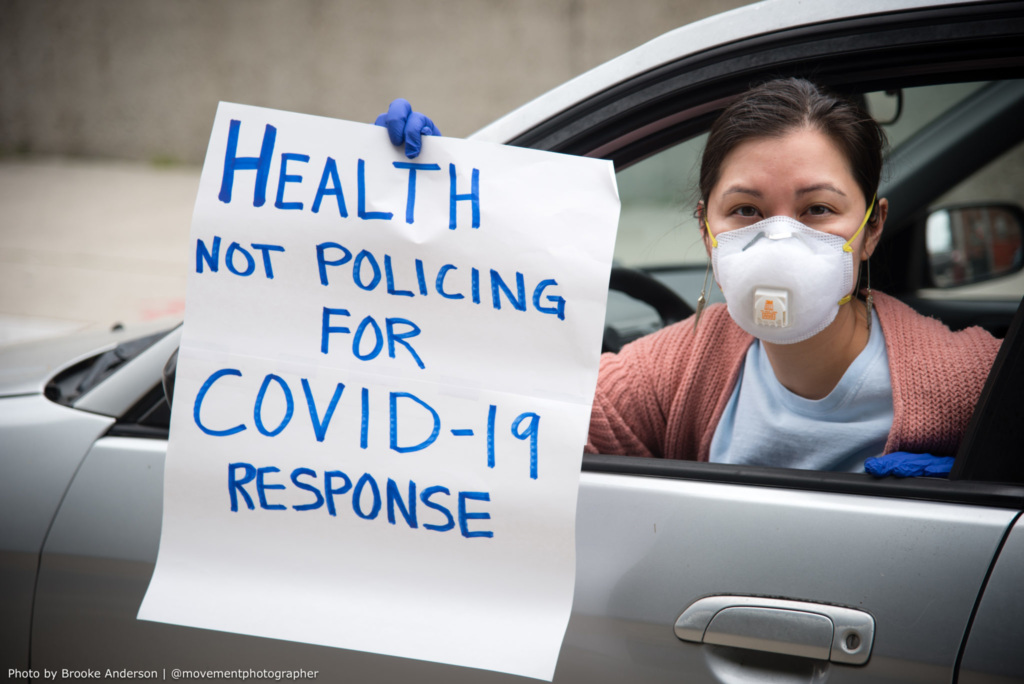

While social math and authentic voices provide valuable ways clarify and contextualize problems, it’s just as critical to clearly communicate your goals or solutions. The more specific, the better. Piatt and her partners did this by illustrating how jail funds could be spent for other, more productive purposes like “providing housing assistance to unstably housed residents, guaranteeing personal protective equipment for frontline essential workers, and ensuring low-wage workers can access paid sick leave.”

She reinforced her point by grounding it in shared values: “Instead of pouring more money into harmful incarceration and senseless punishment, the Board of Supervisors could invest in health and justice for our county,” she wrote, adding “[The Board] has the power to not only stop police murders of Black people, but also to build a more inclusive and healthy Bay Area, through the power of the purse.”

What are your favorite examples of social math? Have you ever used it or another one of the above media advocacy tactics to get an op-ed or letter to the editor published? We’d love to hear about it! Let us know by emailing info@bmsg.org or by connecting with us on Facebook or Twitter @BMSG.

Click below to read the full interview in BMSG’s blog.

Originally published by BMSG

Work With Us

You change the world. We do the rest. Explore fiscal sponsorship at PHI.

Support Us

Together, we can accelerate our response to public health’s most critical issues.

Find Employment

Begin your career at the Public Health Institute.