Philanthropy Must Never Forget What the Pandemic Taught Us About How to Support Public Health

-

Focus Areas

Capacity Building & Leadership, Communicable Disease Prevention, Health Care & Population Health, Healthy Communities -

Expertise

Coalition & Network Building, Leadership Development -

Programs

Together Toward Health -

Strategic Initiatives

COVID-19, Vaccine Access & Equity

Much of the United States seems to have moved on from the pandemic. States and cities are shutting down vaccination and free testing sites, mask mandates have fallen nationwide, and people are streaming into restaurants, bars, and entertainment venues after two years of social isolation.

While some of these developments may be premature, one thing is clear: The nation’s public-health system and the grant makers that support it must not move on from what they learned about how to build a better, more resilient public-health system.

One of the few bright spots during the pandemic was the willingness of government and philanthropic leaders to quickly deploy unprecedented levels of resources to address the crisis. Trillions in federal dollars have gone toward Covid-19 response and recovery, including bolstering the health system and reaching hard-hit communities. Philanthropy contributed more than $6 billion in just the first months of the pandemic — a remarkable mobilization of funding, people, and partnerships to fight a voracious virus that didn’t care about red tape and procedures.

The enormousness and urgency of the challenge required grant makers to be bold, try new approaches, reimagine bureaucratic requirements, and embrace ambiguity. The question now is, will we heed those lessons or return to the status quo?

Perhaps the most glaring truth revealed by the pandemic was the inability of the public-health system to effectively reach and support diverse, multicultural, and rural communities. Even now, these populations, which suffered the most during the health crisis, are lagging in access to information, protective equipment, and vaccines — a problem that will be compounded if Congress fails to approve new Covid-19 funding.

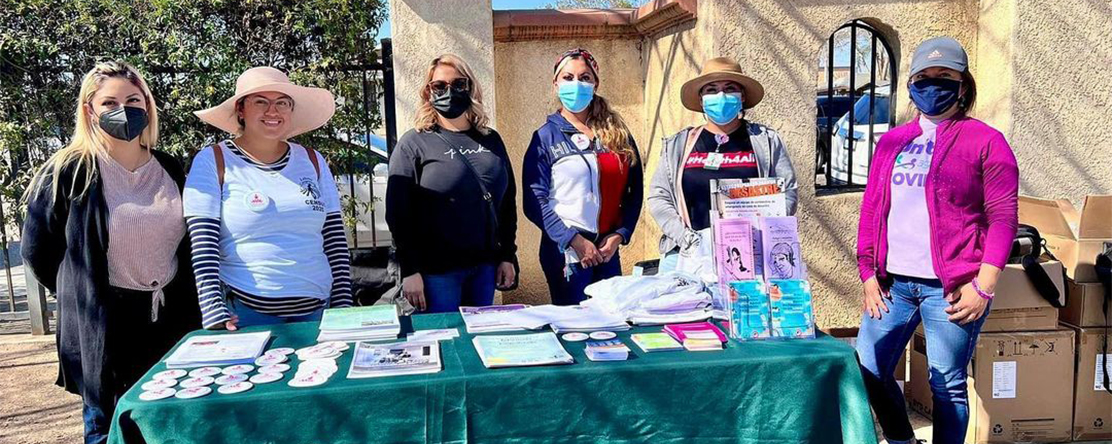

Fortunately, the pandemic has shown that connecting with hard-to-reach communities is possible if philanthropic and government leaders are willing to shed some of their old practices and listen to and trust the community-based organizations that understand best what their neighbors need. I know our public-health system can do better because I’ve witnessed it firsthand as the director of Together Toward Health, a project launched by the Public Health Institute, with support from 25 major foundations, to ensure equitable Covid-19 recovery in California.

Philanthropic and government leaders need to take note. My organization has seen what’s possible in the face of the greatest public-health crisis of our time, and we cannot afford to forget those lessons. By partnering with trust and appreciation for those who are the experts in their own communities, we can build a public-health system that addresses the needs of all people and is prepared to handle any crisis.Susan Watson, Director of PHI’s Together Toward Health

Together Toward Health has so far raised more than $40 million to fund 540 California nonprofits, including local community centers, faith groups, community clinics, and advocacy groups. Based on interim reports, these groups have reached nearly 24 million people, helped vaccinate more than 800,000, and assisted with employment and workforce development for some 230,000. Critically, this work is rooted in how community members live, located where they are, organized by people they trust, and offered in the languages they speak.

So, how did we effectively protect and connect with the hardest-to-reach populations across the state? By applying the simple but essential principles of smarter funding, greater flexibility, and deeper trust in the ability of those doing the actual work to lead it. Here’s what we’ve learned that other grant makers should embrace long after the pandemic ends.

Smarter funding. Many small community nonprofits have trouble connecting to traditional funding channels. So, we knew we needed to simplify the usual funding process and cut out as many barriers as possible. Grant applications were shortened, a percentage of awards were provided up front so that work could begin immediately, and reporting requirements were reduced. This meant funds got out the door and into communities quickly — in days and weeks instead of months.

The impact on grantee work was immediate. “We were in a crisis, so if you have to spend a week doing paperwork, that’s a week we weren’t able to get people scheduled for vaccination and testing — it could be the difference in whether people died or lived in our community,” said Felisia Thibodeaux, executive director of the Southwest Community Corporation, a small organization that serves the often-overlooked Black community in San Francisco. Before receiving Together Toward Health funding, Thibodeaux had to cover two months of her community-outreach workers’ salaries out of her own pocket while waiting for reimbursement from government grants — a steep financial burden that can easily shut down small nonprofits.

Greater flexibility. Given the day-to-day realities of small grassroots organizations, flexibility was critical. Many of the groups we fund have limited staff, some of whom work primarily in the field and can’t reply promptly to emails or attend Zoom meetings. Others have no fluent English speakers in their organizations, and some communities have cultural needs that don’t easily fit into typical funding requirements. For example, multiple grantees used food from a particular region or country to connect with their communities. In San Diego, a grantee partnered with local grocers that carried injera bread to share vaccination information with Ethiopian and Eritrean refugees, and in Shasta County in Northern California, a grantee provided traditional Indian meals at its pop-up vaccine clinics to connect with local Sikhs.

Instead of expecting grantees to conform to our needs, we designed our processes to better fit theirs. That required hosting some meetings in Spanish, providing interpreters for training sessions and meetings, holding check-ins on the phone and even through text messages, and providing low-tech options for grant reporting, such as receiving reports verbally over the phone.

Deeper trust. We trusted our community partners to use their funds effectively, recognizing that the standard tactics don’t work when trying to reach people who are understandably skeptical or mistrustful, such as immigrants and refugees. For example, the leaders of the San Diego Refugee Community Coalition knew that the best way to keep their communities safe was to offer pandemic information in the context of providing for their people’s broader needs. That meant weaving in conversations about vaccinations while helping refugee families get housing support or navigate immigration obstacles.

Other groups used the funds to hire more community–health workers on the ground, pay for client transportation to appointments, or cover creative strategies for getting the word out about the virus and vaccines. One grantee in San Bernardino, El Sol Neighborhood Educational Center, developed a series of comics and videos for youth, featuring the adventures of Captain Empath and his mission to get communities protected through vaccinations. The group’s efforts won a commendation from the White House.

During the past two years, we have learned a lesson that philanthropic and public-health leaders need to embrace for the long term: When the work of local partners is tightly controlled, they lose their ability to fully contribute. They need our trust, confidence, and support to lead.

The Santa Barbara Public Health Department, which worked with several of our grantees, demonstrated the value of this collaborative approach in getting Covid-19 information to underserved populations, including rural farmworkers and people of color. Rather than passing down edicts to community nonprofits, the health department’s staff shared their expertise and resources, including in-depth data on positive test cases and vaccination rates across the county. From week to week, they jointly strategized with the groups about which communities and ZIP Codes needed the most outreach. That collaboration led to the creation of the county’s new Health Equity Alliance — solidifying the department’s commitment to tackling racial and health disparities in partnership with nonprofits working directly with affected communities.

Originally published by The Chronicle of Philanthropy

Work With Us

You change the world. We do the rest. Explore fiscal sponsorship at PHI.

Support Us

Together, we can accelerate our response to public health’s most critical issues.

Find Employment

Begin your career at the Public Health Institute.